When I was about twelve or thirteen years old, my father took flying lessons from his brother-in-law, Kenneth Cross, at the airport in Mt. Vernon, Illinois. My Uncle Kenneth was a science teacher at Mt. Vernon High School, but he was also a certified flight instructor at the local airport. I’m not sure if my father ever soloed. He never became a pilot, but the idea was planted in the back of my mind…anyone can learn to fly.

Of course, I had teenaged things to worry about in the next few years. Would those freckles on my face ever fade? (Lemon juice was suggested by teen magazines.) Would I grow any taller? (Not much.) Would I ever have a boyfriend? (And if I did, what then?) But as I grew older and went off to college at the University of Illinois, those concerns were left behind and a whole new world of possibilities opened up. My first year was in a very tight curriculum with little choice, but when I transferred to the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences as a sophomore, there was time for electives. One that pulled at me was learning to fly. The University had a College of Aviation and its own airport. I was sorely tempted. But Willard Airport was located five miles south in Savoy, Illinois, and flight lessons would take up both time and credit hours. I couldn’t fit it in.

The next twenty years sped along in a rush of responsibilities, marriage, graduation, six children in rapid succession, gradually turning from freelance writing in the few minutes I could spare to full time work in my husband, Chuck’s, insurance agency. All of it was outwardly focused–taking care of family, the business, the community we lived in. Nothing was for me. I hung my Phi Beta Kappa certificate in a frame over the washing machine to help me remember I was a person of value apart from all this.

One day, when we were forty-one years old and our children were teenagers, some in college, Chuck came home to announce that he had met a new friend, Ed Stewart. Ed was a former professional football player with the Chicago Cardinals and currently the principal of a local elementary school, but the most fascinating fact about him was that he was learning to fly. According to Ed, there was a Civil Air Patrol Squadron that had its own airfield in Park Forest, Illinois, a few miles south. Members could take flying lessons at very reasonable rates. “I’m going to sign up,” Chuck said.

“Not without me you aren’t.”

The CAP squadron at Haedler Field was a close knit and fascinating group. There was the president of a small insurance company who really preferred his role as an FAA certified aircraft mechanic to being a company executive. There were flight instructors who had flown in World War II and the Korean War, an auditor for CNA Insurance Company, housewives, salesmen and women, office managers, a wide variety of people, all of whom loved airplanes and flying. Many of them owned their own planes, some of which could be rented. Because its main mission was search and rescue for the U.S. Air Force, it was organized with military ranks for the leaders of the twenty to twenty-five volunteer members. Meetings were held one evening a week, followed by gyros at a strip mall restaurant not far away from the field. Weekends were active with many people taking lessons or just flying to keep up their proficiency or taking off in a group for “$50 hamburgers” at some airport restaurant. (This at a time when hamburgers cost about $3.00.) Everyone took turns as Duty Officer on the weekends, being responsible for operation of the office. If you flew, you had to sign the roster so we knew where you were going and when you expected to return.

Chuck and I were welcomed by the group and immediately signed up for lessons. Getting a pilot’s license meant passing a written test given by the FAA, passing a physical exam to get a medical certificate and taking actual flying lessons from a Certified Flight Instructor. Of the three flight instructors on the field, we chose Colonel Kenneth Soderland, whose real job was as a librarian at the University of Chicago. Ken Soderland’s slight build and quiet demeanor were deceptive. He never talked about his past, but his legend was fascinating. As a teenager, he had lied about his age to join the Army Air Corp during World War II. He became a pilot who ferried B-17s across the Pacific and became known for his unerring seat-of-the-pants navigation. Flying above the clouds in the Pacific where there were no navigational aids, he’d say “I think it’s about here,” descend through the clouds and find the remote island he was heading for. As an instructor he was strict and confident, and he made his students feel confident, too.

Haedler Field was unusual in that it was owned, maintained and run by the local Civil Air Patrol Squadron. Located in farm fields just south of Park Forest, IL, on Illinois Highway 51, it had two runways. The paved east/west runway was short, and the most used 270° approach was over power lines that ran along the Illinois Central tracks just east of the highway. Every pilot who flew there was an expert on short field takeoffs and landings and, even landing on long runways at other airports, we tended to land at the edge of the runway and taxi forever to get to the terminal. There was also a grass north/south runway that was mostly used for flying gliders. The squadron had a glider school for teenage and adult members. On Saturdays and Sundays, planes would take off with gliders in tow, haul them to 2000 feet and release them for silent flights over the corn fields before returning for precision landings on the grass. There was no better way to learn and understand aerodynamics. In later years, several members formed a company to fly banners over the Cubs and White Sox ball parks, using the grass runway. After the tow plane took off, a ground crew would attach the banner to a rope suspended across the runway. The plane would circle around, fly low over the runway with a suspended hook that would catch the banner and off they’d be to the ball game. Something interesting was always happening at Haedler Field.

I took my first lesson on February 2, 1976, in a rented Cessna 150, N45155, passed my written test on May 12, 1976, and had my Private Pilot License issued on August 13, 1976, my father’s birthday. Both Chuck and I soloed on May 9, 1976. What is it like to fly an airplane all by yourself for the first time? Not scary, but there is a funny feeling in the pit of your stomach as your instructor gets out of the plane, the door goes thunk and you taxi to the end of the runway, all alone. Then you tell yourself, “Settle down. You’ve already done what seems like hundreds of landings at this airport before.” You take off to the west, turn left 90°, then left again and you are in the familiar landing pattern. Two more left turns and you are on final approach, lowering flaps, pulling back on the throttle as you keep your eyes on those big red balls on the electric lines along the railroad tracks. Your wheels gently touch the runway and you quickly shove the throttle all the way forward to take off again, chuckling to yourself, “I’m doing it!” When you land the final time twenty minutes later and taxi to the tie down, your friends are there to congratulate you. It’s a good day and the exhilaration lasts.

Even after you soloed, you still had many more hours flying with an instructor, practicing takeoffs and landings at Haedler and unfamiliar airports, crosswind landings, short field and soft field landings, stalls, spins, s-turns, navigation, both visual and by instrument. You had to know how to operate the radio, how to talk to air traffic controllers in the tower or at the FAA’s Air Route Traffic Control Centers. You had to know how to plan your flight, check the weather, and file a flight plan with the FAA. You learn how to do a pre-flight check before you even open the door, making sure that there has been no damage to the plane since it was last flown, climbing a ladder to check the gas level, making sure there is no water in the gas tank and that the pitot tube isn’t clogged. To pass your written exam, you had to learn some basic aerodynamics and meteorology, but to be a safe pilot you had to develop practical application of that knowledge. There is no better way to grasp basic aerodynamics than to practice a stall, where you pull back on the wheel into a steep climb until the plane can no longer fly and the engine stops. It is very quiet when the engine stops. To recover, you put the nose down and dive until the engine starts again. Your instructor directs you higher and higher, then puts the airplane into a spin. You learn how to recover by concentrating on the instruments and not on the disorienting landscape out the window.

Cessna 172B – N7503X

We were hooked. Even before we had our private pilot’s licenses, Chuck and I bought our first airplane, N7503X, a Cessna 172B, manufactured in 1960. I recently looked it up on the FAA’s website.

It is still flying. Because of mandatory maintenance, private airplanes can fly safely for years and years.

Search and Rescue

The primary purpose of the Civil Air Patrol was search and rescue. There was also an emphasis on education, particularly of young people who had the urge to fly, but no opportunity, and many squadrons concentrated on that. But, because the Park Forest Squadron had its own airport with many airplanes and a well-trained membership, we got more calls than most. Remember, this was the 1970s. There were no artificial satellites orbiting the earth, no GPS to guide you. After 1972, Congress passed a law requiring all U.S aircraft to have an ELT (Emergency Locator Transmitter) installed in the tail of the aircraft. This was the result of a crash in Alaska of a plane carrying U.S. Representative Hale Boggs which was never found. The problem was that those early ELTs were prone to false alarms due to hard landings. The radio signals at 121.5 MHZ were not audible to human ears. Pilots banged their planes down, taxied to the hanger, closed the doors and went home to bed. Meanwhile, the crash warning was picked up by the Air Force at Scott Air Force Base in southern Illinois and the call went out to the Civil Air Patrol to search for the aircraft.

Our early experiences with search and rescue were ELT alarms. If there were no reports of missing flights or accident sightings, our Squadron leader would know the ELT alarm would likely come from an airplane on the tarmac at some airport, so he would call two or three members to get into the air to investigate. By homing in on the ELT signal, it usually took only an hour or so to find the aircraft, locate the owner and get the alarm turned off. While we might grumble about getting out of bed in the middle of the night because of a rough landing, these calls were excellent training for more serious alarms and sharpened out navigation skills. Our first big search came in September 1976, when a plane was lost in the deep woods of the upper peninsula of Michigan. The Michigan Wing of the CAP had been searching those miles of green, gold and brown trees for a week and they were exhausted. We were called to take over so they could rest. This type of mission called for a visual search with the pilot navigating the search pattern and the passengers looking out the window for any break in the trees or any airplane debris. We searched until we were exhausted, too, but never found the plane. It was finally located the next winter by hunters.

We did have our saves, however. One day there was an ELT alarm in the farm country not far from our airport. Chuck was on the plane that spotted an aircraft upside down in a corn field and was with the ground search team that found the pilot and passenger, who had been hanging from their shoulder and seat belts for more than a day. The pilot was dead, but his female passenger survived and was rushed to the hospital. That save made up for a lot of middle of the night false alarms. Another time, we were called to search for a plane that had disappeared after takeoff from DuPage Airport. One of our members was a helicopter pilot whose boss let him use the company craft for search and rescue. He started the engine and two other pilots and I jumped in as spotters. It didn’t take long to find the crash a mile or so from the runway. We landed and jumped out ready to rescue, but we were too late. Both the pilot and passenger had been killed in the crash.

Because we saw what could happen when things went wrong, I think most of us were safer pilots than most. Our instructors pounded into us, “You can handle one thing going wrong, probably you can handle the second thing, but you can’t handle the third. Pay attention and don’t take chances.” You’d be flying along with your instructor on a perfectly serene flight and he’d reach over and pull the throttle and the engine would stop. “You’ve lost your engine,” he’d say. “Now what are you going to do?” There was emphasis on proficiency and experience. CAP required every pilot to be evaluated by a flight instructor twice a year and failure meant you could no longer use the airport. We all felt that you had to log at least 50 flight hours per year, or you were not safe to fly. We learned to evaluate any pilot we flew with. As student pilots we assumed that anyone with a license knew what they were doing. Chuck learned the hard way that wasn’t true. He took a ride with a pilot he didn’t know well for a short trip to South Bend, Indiana one day, but on the way back, the pilot got disoriented and froze up, afraid to land. It took several scary minutes for him to get control of himself and land at the nearest airport where he decided to stay until the next day. Chuck called me to come get him and drive him home. Lesson learned. Be careful who you ride with.

Fun, Fun and More Fun

Despite our serious purpose, most of our flying was just for fun. Chuck and I did use our plane for business, visiting clients, attending insurance company meetings as far away as Acapulco, Mexico, and Napa Valley in California, but mostly we poked holes in the sky with our pilot friends.

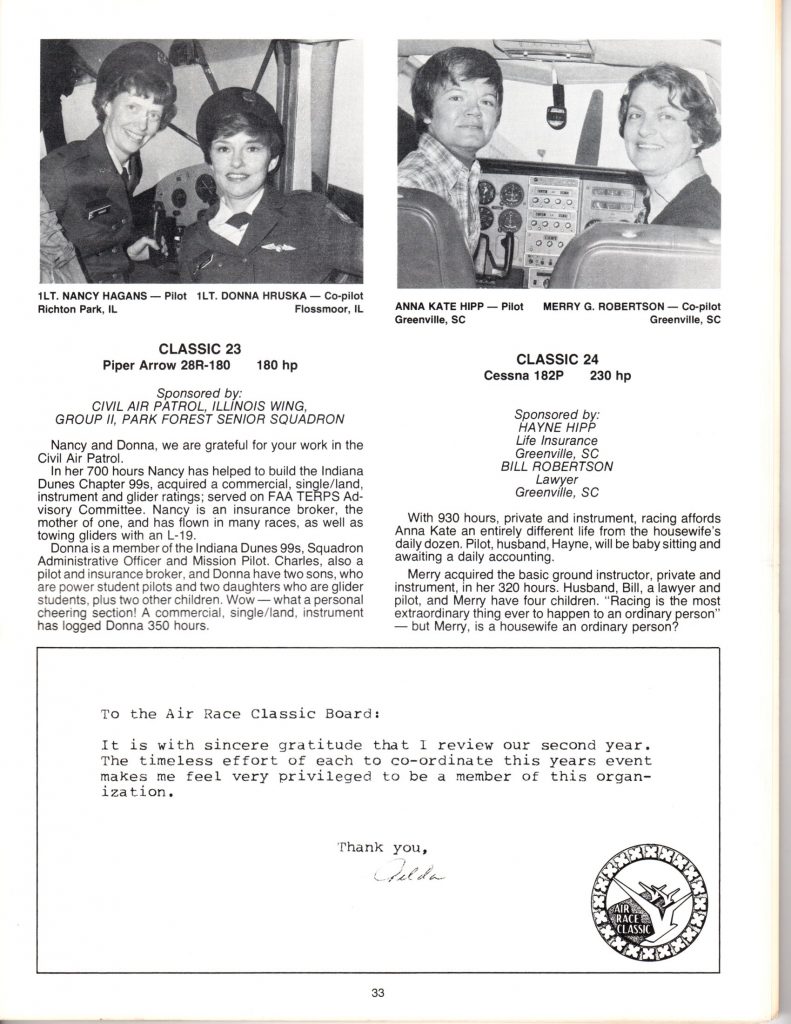

One Saturday in the late 70s a bright yellow Piper Arrow landed at Haedler. A group of angry officers marched out to find out who this interloper was, landing without permission on our CAP only airfield. Out climbed an attractive woman with red hair and a big smile. She was from northern Indiana and had always wondered about this little airport and decided to land and see what was going on. By the time they had tied down her plane and walked her to the office, she had charmed the anger right out of them. Nancy Hagans became an active qualified member of CAP. Nancy loved flying. She was an active member of the Ninety-Nines, a women’s pilot organization. She admired the early female pilots who proved that gender had nothing to do with flying skills. Shortly after becoming a part of the Squadron she proposed that she and I race in the Powder Puff Derby, which the year before had been renamed the Air Race Classic. We would use her plane, which was faster than mine. This was more complicated than it sounds. The winner wasn’t the first plane that landed because all the planes were different. Some had bigger faster engines, some had better aerodynamics. The race was handicapped according to the average speeds of the make and model of airplane each team was flying. The test was not who had the fastest plane. It was who were the best pilots. By taking advantage of the winds aloft and good navigation skills, a team might land last and still be the winner. The race was about 2500 miles long and took four days. It began in Las Vegas, NV and ended in Destin, FL, following a circuitous route as far north as Casper, WY. We had to hire our own weatherman to advise us on wind speed and direction at various altitudes and along different routes. We had to pay for gas, hotel rooms, food and other necessities. We needed money.

No Go-Fund-Me accounts in those days. This required brochures, telephone calls and shoe leather. Our brochure had our picture in our uniforms, explained the race and estimated we’d need $2,000. The national and state Civil Air Patrol each pitched in. We hit up our local bank president, all our members and all our friends and came up with the cash. I took a few lessons in the Piper Arrow and we were off. Race headquarters was in a Las Vegas casino that had essentially been taken over by a bunch of women pilots of all ages. Some with lots of flying hours, some experienced racers and some inexperienced like us. We didn’t care. We were thrilled to be among them. The route was all over the middle part of the country, from Las Vegas, to Grand Junction, CO, Casper, WY, North Platte, NB, Olathe, KS, Burns Flat, OK, Hot Springs AR, Gulfport, MS and finally Destin, FL. The race was a four-day blur, talking to our weatherman, deciding the best time to take off, when to hold back for better winds, falling into bed at night exhausted. In other words, more fun than we’d had in a long time. Once we were the second to land, but in the end, we were nowhere near winning, not that it mattered to us. The Air Race Classic had made arrangements for us to stay at Pinnacle Port, a new condominium development in Panama City, FL, not far from Destin, and many of our Squadron members were there waiting for us. Big party! We were heroes.

Because we had such a good time there after the race, Chuck and I eventually bought a condo at Pinnacle Port in Panama City and that became the destination for many of our CAP friends for long weekends laying on the beach, making our first stop after landing at oyster bars selling raw oysters for $2.50 a dozen.

We felt we’d worn a sky highway between Haedler Field and Panama City airport, and we’d race to see which plane got there first. Those were heady days with good friends, good deeds and adventures in the skies, many of which I’ll recount in my next family history story. During that time two of my sons, Brian and David, got their private pilot licenses and joined the sojourn to Pinnacle Port. Both my daughters, Jennifer and Susan Elizabeth, took glider lessons and Susan Elizabeth was featured in the local newspaper when she got her glider license at age 14.

And so, we proved it was still so. Anyone can learn to fly.

Donna Mae Glenn Hruska Hunt

November 1, 2019

Rose & Charles Hruska – Naturalization Talk

Rose & Charles Hruska – Naturalization Talk

I have never forgotten that day Paul and Marty had crashed their plane and died. I remember when my parents came to tell us what had happened. Paul, the son, was a CAP cadet with us. It was my 1st real experience with death and they died doing something I loved. It was also when I learned what alcohol can do to you when left unchecked. My parents didn’t hide from us why they crashed. They wanted us to learn from that horrible experience. And they were right. It left a lasting mark on me. They were good people and I have thought of those life lessons many times over the years.