Recently, we had the interior of our house painted. This, of course, meant all the furniture would be moved, including the three china cabinets. The china, crystal, silver, vases and other decorative objects had to be wrapped in paper and packed in boxes. Worse, when it was all finished they had to be unpacked, washed and polished. As I stood at the kitchen sink, up to my elbows in soapy water, with the smell of the rinse water vinegar clearing my head, my thoughts turned to my sister, Judith. So I took a break and called her.

“Judith, I’m washing all the crystal and china, so, of course, I thought of you. You wash dishes more than anyone I know.”

“That’s true,” she answered. “I have an advanced case of the dish disease.”

Judith has sets of dinnerware for every season. At least four times a year, she hauls out the appropriate set from the pantry, washes them and puts them in the kitchen cabinets. Then she packs the old set away until next year.

“I realized recently that over half of my pantry is filled with dishes,” she confessed. “And I don’t even cook. I have three lists of missing pieces of china in my purse at all times, just in case I come across one when I’m out shopping. For years I refused to buy any newly manufactured pieces of Desert Rose, because they are now made in the Philippines and no longer are hand painted. Finally, I slapped myself and realized nobody knew that but me. I’ve become obsessive.”

My sister Betty is equally afflicted. She admits to at least seven sets of china and dishes, plus Waterford crystal stemware, sterling silver flatware and numerous odd pieces of crystal vases and barware. Once, in St. Petersburg, Russia, she almost missed the second half of the Bolshoi Ballet, because she discovered a woman selling distinctive blue and white Russian china at intermission.

We agreed, all three of us are obsessive, and it’s our mother’s fault.

We’re not sure if it started with her, but she had an advanced case. Maybe she was infected by her mother. I remember going to my Grandmother Chapman’s house as a child. My grandmother had a small house in Tamaroa, a town in southern Illinois. Looking back now, I don’t know what she lived on. Social security, I guess. But then she owned her house, raised chickens and had a vegetable garden. But in spite of what would be classified as poverty now, in the dining room she had an oak china cabinet with glass doors on the left side and a fold out secretary desk on the right. Her best china pieces were in that cabinet. Her house also had colonnades, something you don’t see any more, separating the dining room from the living room. These were built-in cabinets with glass doors. I remember pressing my nose against the glass doors, (I wasn’t allowed to open them) staring at the hand painted bowls and plates. Sometimes, for family dinners when we’d all sit at her round oak table, a few of those pieces would come out, but they were treated carefully. So, maybe my mother came about her china passion honestly, at her mother’s knee.

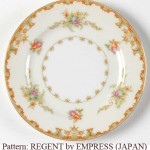

My mother had very little money to indulge her china passion in the early days of her marriage. My parents were married in 1929, when they were still in college, in Carbondale, Illinois. By the time they graduated in 1933, there were very few jobs. My father managed to be hired as the principal of the combined elementary/high school in Oakdale, Illinois. That sounds grand until you find out that the population of Oakdale was only about 250. The elementary school had two rooms, one for grades 1-4 and the other for grades 5-8. The high school probably had less than 30 to 40 students. My father was able to supplement his income by showing movies in the school assembly hall occasionally and charging five or ten cents for admission. At some point in that period, my mother was able to buy a complete set of pre-war Japanese china. The pattern was Regent by Empress Japan and it is still my favorite of all. She probably bought the set at the Famous Barr Department Store in St. Louis, the only store where you could buy something as fine as this.

That was the end of her china collecting for a number of years. My father was a serial entrepreneur. Before he got the principal’s job, he had been editor of a local newspaper in Flora, Illinois. Apparently, I slept in a cardboard box at the paper while they tried to make a go of it. He also had made and sold vanilla and lemon extract. For years, we had a large supply of tall bottles of extract for baking and cooking. Showing movies in the high school seemed a good idea, but didn’t provide much income. He tried it on a larger scale by taking the movies to somewhat larger small towns. There were very few theaters in rural Illinois at that time. He bought an enclosed trailer that he pulled behind his car. It was loaded with folding chairs, a screen, a projector and tent sidewalls. In the summer, he would pull the trailer to a small town where he had rented a lot. He’d pay a local boy to help him put up the tent and set the chairs. He sold tickets, ran the projector and after it was over, packed it all up again and drove home. The next night he’d go to a vacant lot in another small town. Gradually, he found buildings to rent and set up a regular schedule. Some towns had movies on Tuesday night, some on Fridays or other nights of the week. He began to make enough money to quit teaching, but it was not providing a munificent living. Then came World War II, with gas and tire rationing. It looked like he would be drafted, even though he was 35 years old with three children. Just before he was to report for his physical, Congress lowered the draft age and he didn’t have to go. Even so, to do his part, for a time he drove to the munitions plant outside of Carbondale to work a late night shift after a show.

My mother helped by selling tickets, eventually managing some theaters herself. She also took care of the money. When my father expected to be drafted, he moved us to Tamaroa so we would be near my mother’s family while he was gone, but he kept banking in the little home town bank in Oakdale. It had not gone under during the Great Depression like many other banks. My parents felt it was worth the 22 mile drive to trust their money to a safe bank. My sisters and I had many wild afternoon rides, as my mother sped to put the money in the bank.

Finally, the war was over and life began to return to normal. At one point, my father went to Washington, D.C. on a business trip. Driving through Ohio on his return, he saw something that was to change his life: a drive in theater. I remember how excited he was when he returned as he sat at the kitchen table, explaining the idea to my mother. He wanted to build a drive in theater on highway 51, outside of town. He even wanted to call it the Melody like the one he had seen in Ohio. My mother was skeptical. After all, she had been through a number of his big ideas and, at last, while not rich, they were secure. Of course, he talked her into it. He acquired the land, hired a carpenter and began building. I don’t know how much it cost, but I suspect it was everything they had and a lot of promises besides. As the opening approached my mother became more and more anxious. My father assured her, “It’s either going to be successful or it’s not. If it’s not, we’ve been broke before. We can do it again.” That wasn’t exactly what she needed to hear. On opening night I’m sure her stomach was in a knot as we all piled in the car to get to the theater in time to open the box office. To our surprise, cars were lined up down the highway and the state police were there directing traffic.

Finally, they were a financial success. More drive-ins followed and there was money to spare. My father used to tease my mother by telling people how she had cried on her 40th birthday because they still were not a success and now it was probably too late. I noticed, though, that he only told that story years later, after success had finally come. With money no longer a problem, she could indulge herself, and she started to buy the crystal stemware she had always wanted. Her chosen pattern was Etched Candlewick. After she died, my sisters and I searched everywhere. We discovered that several companies used that name, and Judith, ever persistent, was able to find pieces to fill in. For holiday dinners, our mother always set the table with her china, crystal and silver, washing every piece by hand afterward, and getting very nervous if we tried to help. Even after we were grown women with houses of our own, she was sure we would break something. And, of course, occasionally, we did.

She liked hand painted stoneware for everyday use, often buying colored water glasses to match. My father used to tease that there were boxes of dishes under every bed. That was true. Her dream was to leave each of her daughters a set of everyday dishes, and she did.

Like most brides in the 1950s, I registered my china, crystal and sterling silver patterns before my wedding. Family and friends were generous and I had a complete setting for eight right away. Over the years I filled in missing pieces. My husband, Chuck, was a proud Bohemian and knew that Bohemian lead crystal was the finest in the world, but it was hard to come by in the United States. Bohemia was part of Czechoslovakia, captured first by Nazi Germany, then “liberated” by the Russians to become part of the Eastern Communist Block. In the early 1980s, we joined Chuck’s parents and met our son, David, in Vienna, Austria, where he was studying, and ventured into Czechoslovakia. That in itself was an adventure because we had to cross a mile wide no-man’s land with barbed wire fences and soldiers patrolling with Uzis and German shepherd dogs. Once inside the country, Chuck’s mother’s relatives were happy to show us around and the first place we wanted to go was the state store that sold Moser crystal. A Czech citizen couldn’t buy anything in that store, one, because it was expensive for them and, two, because most everything sold for western currency only. We were stunned by the beauty and artistry of the glass, hand etched and trimmed with gold. The most elegant was stemware in the Paula pattern and we managed to buy eight water goblets at a bargain. To understand the bargain, you need to know that the Czech government, like all communist countries, set an artificially high value on their currency, the crown. Everyone knew that it wasn’t worth that much in exchange for western currency, so every time Chuck walked down the sidewalk in Prague, a dark figure would fall into step behind him and whisper, “Psst, want to buy crowns? Very low price.” By the time we got to the Moser store, he had a pocket full of black-market crowns. By buying other items with U.S. dollars, we talked them into letting us pay for the water goblets in crowns that worked out to $50.00 a glass. When we got back to the west we found the same glasses, when you could find them, were selling for over $300.00 each. Today, if you can locate them, the price is $350.00. That was it for Chuck. He now had the dish disease, and every time he went back to Czechoslovakia, he bought more, until we had a stunning collection. On that first trip, we also took back Moser crystal as a gift for our son, Chuck, in appreciation for his manning the insurance agency while we were gone. Boom! Another victim. Now he started collecting Moser wine and cordial glasses. Some years later, son David and his wife, Helen, went to Prague on their honeymoon, and what did they buy? You’ve got it…Moser crystal. You see how this happens. It’s just like a virus.

Many years after Chuck’s death, when I remarried and moved to California, all the china and crystal moved with me. That was when I discovered that my new husband, Arlon, had a complete set of his mother’s china, a delicate Havilland china pattern from Limoges, France, and a silver flatware service for twelve packed away and unused. This Thanksgiving, we used it to serve a holiday dinner for his children. They didn’t remember ever seeing it before. I offered to buy a few extra pieces to finish it off. Perhaps, more converts?

After my conversation with Judith, I forgot just which patterns she had, so I sent her an e-mail. She replied,

“I have Desert Rose, Old Country Rose and Christmas Tree by Spode and the Ivy pattern plus the Etched Candlewick. I haven’t checked under the beds but that is pretty much it. I do have a set of everyday dishes which are international stoneware and a set of Chinese dishes plus a set of Lenox Winter Carnival everyday dishes and a partial set of Easter dishes for Easter. Finally I have a Tea service of Royal Albert pots and 10 assorted tea cups from the 1930’s, 40’s,50’s, and 60’s.

I was feeling pretty good when I started to answer this question but as I list what I have, I realize I have either inherited a gene out of control or I may be out of control in the dish department. I believe the best course for me to take is to deny any knowledge of this question or the answer especially if Bill Leonard (her husband) is in the room.”

Our telephone conversation concluded on an interesting note.

“Remember when the three of us were dividing up mother’s things?” I asked Judith. “When the time comes for my children to divide the spoils, what do you think they’ll choose first? The jewelry or the china and crystal.”

“No question,” she replied. “The china, of course. They’re in this family, aren’t they?”

Postscript: After writing this account, Betty and I, with husbands, went to Judith’s for Christmas. Snooping around, Betty and I discovered that Judith had lied (or more charitably, miscounted). We found a set of the blue Russian dishes and at least two more pottery sets, with matching colored glasses. We weren’t able to look under her bed, but we have our suspicions. Apparently, the dish disease affects your moral character, or at least, your ability to count.

I must run now. I’m filling out a Replacements, Inc. Internet order for a Gorham Wedding Ring crystal wine glass and a sterling silver sugar spoon. Just filling in, you understand.

How to Care for Your China, Crystal & Silver

My mother was right. You have to do it by hand. Never use the dishwasher. Most fine china is decorated with precious metals, mostly gold or platinum. Harsh dishwasher detergents will damage that trim and etch your crystals in patterns you won’t appreciate. I have never found it a chore to wash by hand, even after a big dinner party. It gives you time to reflect and relive the evening.

Washing China and Crystal

Rinse food and drink as soon as you can after the meal. Food, particularly acidic foods can cause stains that are impossible to remove. Fill a plastic tub with warm water, or, if you don’t have a tub, line the bottom of your sink with a soft towel. Add mild dishwasher detergent. I like to add a couple of tablespoons of vinegar to both the wash water and rinse water to be sure everything sparkles when I’m done. Move the faucet out of the way if you can, and slip a few pieces at a time into the water. Don’t crowd, or you risk scratching or chipping. Remove jewelry or wear rubber gloves. Rinse each piece as you wash it in a basin of warm vinegar water and set on a soft towel to drain. Dry with a lint free dish towel and hold each piece against the light to make sure you didn’t miss a spot (and to admire the sparkle).

Washing and Polishing Silver

Once again, rinse as soon as you can after the meal. Some foods tarnish silver. Use the same washing process explained above, paying particular attention to drying. Count each piece as you put it away in the silver box. Heaven only knows how many silver spoons are lost in our landfills, after careless cleaners scraped them off with the food scraps. Store your silver in a silver box or in tarnish proof cloth holders. Hagerty makes paper protection strips that really work. Just slip one in box with the silver and it will still be shiny the next time you want to use it. These also work in china cabinets where you store silver serving pieces.

If your silver does become tarnished, wash and dry it first, then use a polish that is specifically designed for silver, not a general metal polish. Wash again and dry with a soft cloth. Years ago I found a metal plate from Quicksilver International that works with very hot water and Arm and Hammer Washing Powder to take the tarnish off of silver with hardly any rubbing. It makes the job very easy.

The Most Important Rule

The most important thing to remember is: Use it. Don’t pack your fine things away in a box. Don’t hide them under the bed. Don’t “save it for good.” As my brother-in-law Ron Haxton says, “Good is here!” As a matter of fact, your sterling silver looks more beautiful the more it is used. The little scratches that accumulate are called “patina,” and over the years they add a soft glow that show that this set belongs to a family who loves fine things. If you break something, there are wonderful companies like Replacements, Inc., that can find matching pieces to fill in for the casualties. My mother would be proud of you.