Everyone in the extended Hruska family tries to make it to the farm on the third weekend in October every year, but it has occurred to me lately that maybe some of the younger generations may not know why the farm exists and why it is so important to show up. Maybe a little background will help.

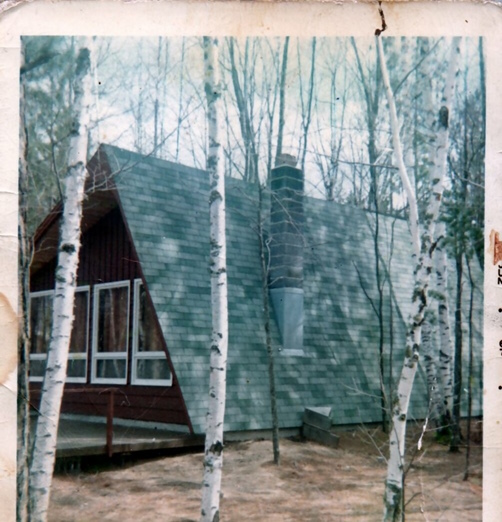

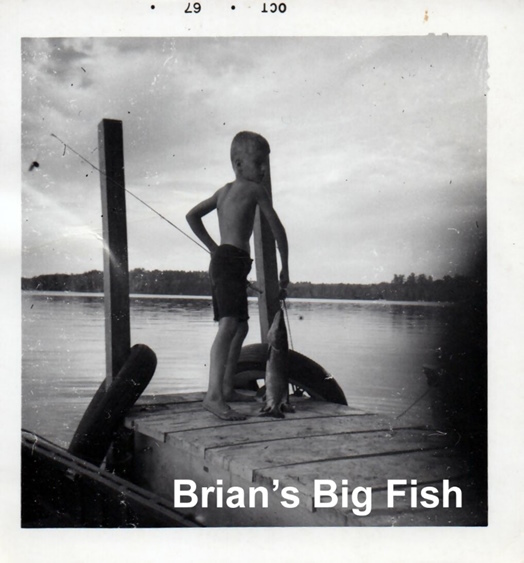

Our husband/father/grandfather, Charles Joseph Hruska Jr. (Chuck), was the son of immigrants from Bohemia who grew up in Berwyn, Illinois, an urban suburb of Chicago populated by first and second generations Czechs and Slovaks. He loved hunting and fishing and being outdoors. How that happened I’m not sure. It wasn’t in his family tradition which tended more toward family gatherings with pork and dumplings and other Bohemian dishes. Perhaps it was a trip he made as a boy to the Wisconsin woods with family members where he caught his first fish. From the first days of our marriage, if a group of guys were going on a camping and fishing trip, he was first in line. He greeted the dawn in cold duck blinds in Grafton, Illinois, near where the Illinois and Mississippi rivers meet. He was fishing on Kentucky Lake or flying into remote fishing campsites in Canada. He loved deer hunting in southern Illinois and pheasant hunting in northern Illinois and South Dakota. When our children were young, we bought an A-frame cottage on Post Lake in northern Wisconsin where everyone learned to swim and fish off the dock or from a rowboat. In winter when the lake was frozen, he, sometimes with his sons, but always with his black lab, Maxie, bored holes to ice fish. He made sure all of our six children knew how to clean a fish and how to cook it over a campfire if they were in the wilderness.

We would load all six of the children in the back of the station wagon in the late afternoon to start the six-hour trip to Post Lake, stopping in Milwaukee at a drive-through McDonalds for hamburgers and cokes. Even in winters with the snow waist deep, pulling our snowmobiles behind us, we’d make the trek for winter fun. My parents, May and Frank Glenn, bought an adjoining lot and added a trailer home and a motorboat. All the children learned to swim and ice skate. In winter, one snowmobile would roar around the trail while Chuck changed the sparkplugs in the other one.

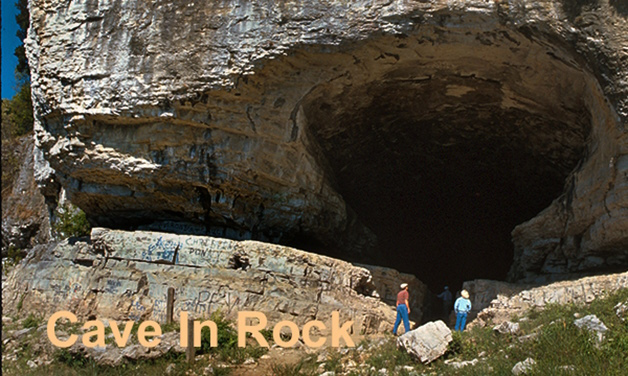

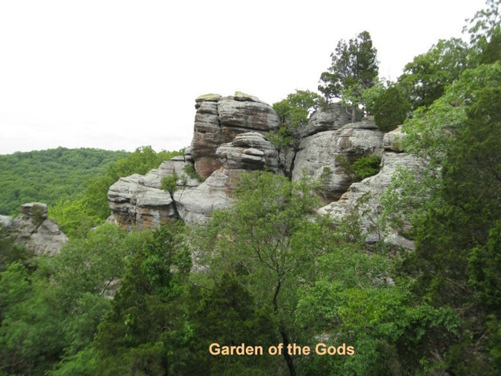

But children grow up. Teenagers have more important things to do with their friends than going to the cottage with their parents and eventually we said goodbye to our Post Lake friends and sold the cottage. Our children were off to college and then to careers and families of their own, all in cities. Chuck began to worry that his grandchildren wouldn’t know or appreciate nature and the outdoors. Maybe by living far apart they wouldn’t know each other well. Maybe he couldn’t teach his grandchildren to fish and hunt. He decided to fix that. We needed a family property that was in the wilderness but easy to get to. He started his search Hardin and Pope counties, Illinois’ least populous counties in the south where he had gone deer hunting for many years. Others might think, “Illinois? Isn’t that flat corn and soybean country?” It is, mostly, but the southern counties that border on the Ohio River are a different world altogether. Often called the foothills of the Ozarks, the land is hilly with limestone cliffs and outcroppings, caves, and creeks. The Shawnee National Forest sweeps across the state from the Wabash River in the east to the Mississippi in the West interspersed with tiny towns and occasional farms and includes Garden of the Gods Recreation Area.

Garden of the Gods is in Hardin County as is Cave In Rock State Park on the Ohio, where pirates once robbed settlers who were rafting down the Ohio River. You can hike, bike or ride your horse on the River to River trail from the Indiana border to the banks of the Mississippi River, passing portions of the Trail of Tears over which the Cherokee walked to Oklahoma in the 1830s.

After searching for months, Chuck finally found what he was looking for: 85 acres of hills, creeks and forest that hadn’t been farmed or lived on since the 1950s. He bought it at auction literally on the courthouse steps in Elizabethtown, Illinois. He was the only bidder. Exploring it was an adventure in itself. Some of it was part of the last 2% of original prairie left in Illinois. The wildlife included deer, wild turkeys, cougars, bobcats, red fox, silver fox, beaver, raccoons, and groundhogs.

The most intriguing was a log cabin and an old barn, both in a sorry state of disrepair. From a book on log cabin construction techniques that we bought on a visit to George Washington’s home at Mt. Vernon, we estimated that the cabin had been built around 1837. Sometime later an additional room had been added. And so, the restoration began. Gradually, he hired a local handyman to help him uncover the original cabin and carpenters to salvage and rebuild the barn.

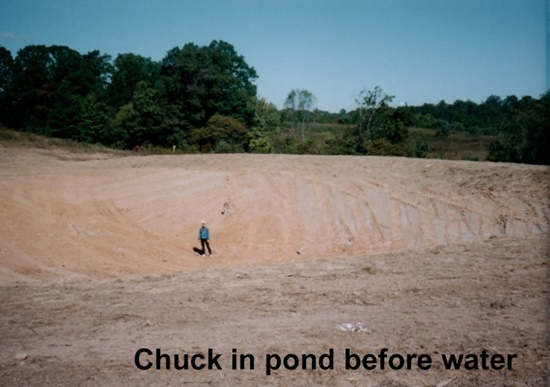

He had a pond dug and stocked it with fish. Hiking trails were cleared.

Controlled burns were organized to clear the forest floor and destroy invasive plants. County water and electric lines were available on adjacent roads but were ignored. To get to the site of the cabin if you didn’t have a four-wheel drive vehicle, you hiked more than a mile, fording creeks, and climbing steep hills. One creek was renamed Bumper Creek after Chuck lost his bumper trying to drive his Audi sedan across.

The tradition of “Going to the Farm” was established. Every April and every October the family gathered. Some brought tents and camped. Some slept at nearby Bed and Breakfasts. Once the barn was rebuilt, grandchildren loved sleeping in the barn loft. For grandchildren The Farm was heaven.

They loved the tire swing on a twisted old tree near the cabin. They built forts in the forest. They splashed in the creeks and climbed trees. There were years when paintball fights were the big entertainment. One October we had a pumpkin carving contest. There were board games that lasted for hours. All meals were cooked over a campfire and tall tales were told around that campfire at night. During deer season, competition was strong to see who was the most successful hunter. Hammering echoed through the woods as sons and grandsons built deer stands in the trees along the wildlife trails. In both bow and arrow and shotgun seasons, families would stock their freezers with venison and their refrigerators with venison salami.

As the years slipped by, adjacent property came up for sale and the farm grew to 185 acres. But always, it was wild, and children grew up understanding nature, catching their first fish in the pond, and hiking in the woods, much to their grandfather’s delight. To make sure that the farm stayed in the family, ownership was transferred to an irrevocable trust that couldn’t be broken for over 100 years.

He wasn’t giving us any option. We were to be together whether we liked it or not. Sadly, in 1998 he died, after he tripped and fell down a short flight of stairs, causing brain damage from which he could not recover. But, in a sense, he is still with us on those trips to the farm. We created a cemetery and buried him there on a hill where the sun rises over the trees in the east and sets in the forest over his shoulder. No family member goes there without a stop to remember the grandfather who brought them together.

The cabin has been much improved in the last 20 years. Scheduling has become more complicated as everyone has grown and scattered, so we only meet once a year in the fall. There we are on the third weekend in October every year. Sometimes families have other commitments, but there will be 25-40 of us, the number growing every year. Most of the grandchildren are married, engaged, or committed to a partner. We laugh that before anyone can be brought into the family, they have to pass the farm test. If they are squeamish about hiking or cooking over a campfire or unable to function without an internet connection, they probably aren’t going to last.

Last year one grandson and his wife brought an enormous new tent. Callan, one of newest great-grandchildren at 10 months old, had a wonderful time exploring. The rough terrain didn’t slow him down at all. There was competition for grilling space and some little people were learning how to toast marshmallows for smores.

Brian brought his telescope because this is one of the few dark sky locations in the country.

It was a wonderful weekend, perhaps best summed up by Theo, who at five years old, didn’t remember his pre-pandemic first visit to the farm. In the glow of the campfire, I heard him ask his mother, “Why does everybody here like me so much?” “Because we’re family,” she answered. That’s what family does.” “Ah,” I thought, that would make your grandfather so proud.”

© Donna Hruska Hunt 9/16/2023

196X – Flossmoor Town Parade

196X – Flossmoor Town Parade

What a great story and legacy!